As the year draws to a close, internal communication within organisations becomes more concentrated. Boards look to confirm whether results have been realised, markets seek clarity on the next direction, and management, working against the clock, revisits both language and timing. Year-end messages typically revolve around growth, investment, and the year ahead.

Yet, amid this rhythm, some leaders choose to send an open letter or internal address to all colleagues around Christmas, deliberately avoiding discussions of performance or strategy. They shift the focus away from work itself, turning instead to topics like time allocation, family companionship, and gratitude for the year’s efforts. These messages are not lengthy and do not provide clear instructions, yet they are often remembered by employees and even recalled years later.

What makes such communications stand out is not whether the language is moving, but that they appear at a moment when “one isn’t supposed to speak this way.” When most managerial language points toward summaries and outlook, some choose to temporarily shift the focus away from results, returning the organization to a more fundamental state—a group of people under pressure who also need to be trusted.

From a reputation management perspective, this is not an emotional choice but a deliberate leadership communication strategy. Festivals become a time of low confrontation and low defense, allowing leaders to reposition their speech and redefine the organization’s shared understanding of “what matters.”

Leadership Communication That Doesn’t Focus on Performance

At this year-end milestone, when a company’s top decision-maker personally issues an internal open letter or address that deliberately avoids performance, goals, and strategy, the message itself is not neutral. Its impact does not come from the content but from the speaker’s decision to “not exercise power” at this moment.

Most of the time, managerial language functions to drive action, allocate resources, and set evaluation standards. However, when those in decision-making roles actively pause this language system during high-pressure moments, it sends a clear signal to the organization: short-term performance will not be re-examined at this time, and trust will not be deducted because of a pause.

Such a message only holds true when spoken by those who genuinely hold resources and evaluation authority. For senior executives and core talent, this means that risk assessment during this period is clearly reduced, and individuals do not need to continuously prove themselves during the holidays.

This is not emotional comfort but a governance choice. When power chooses to temporarily remain unused, the organization finds it easier to restart at the next milestone.

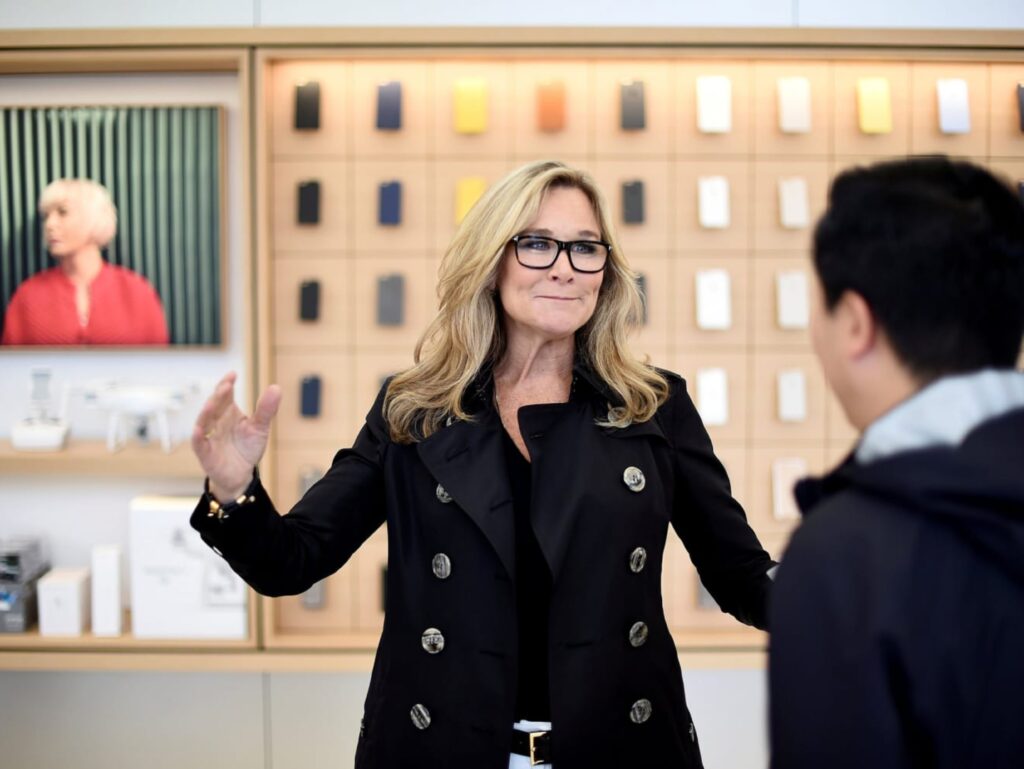

Angela Ahrendts: Making Trust an Expected Daily Reality

During her tenure as Senior Vice President of Retail and Online Stores at Apple, Angela Ahrendts was responsible for the operations and cultural direction of over 400 Apple Stores worldwide. This role directly managed front-line personnel while influencing brand perception and talent retention.

Upon joining Apple, her definition of the retail department differed from external expectations from the outset. Compared to sales efficiency and performance per square foot, she cared more about how employees felt treated when they walked into the stores each day. In multiple public speeches, she repeatedly emphasized that corporate culture is not about policy documents or slogans on walls but the result of accumulated daily behaviors. She clearly stated, “Culture isn’t something you write down. It’s what you choose to do when no one is watching.”

In Ahrendts’ context, customer experience does not start with the customer but with employees. She pointed out this sequential difference directly: “Many talk about customer relationships, but the first relationship you should build is how you treat your own employees.” This approach pushed the responsibility for retail performance one layer deeper into the organization, preventing managers from attributing service quality solely to processes or training.

This thinking was later concretely implemented in the transformation of Apple Stores. In 2017, Apple launched the “Today at Apple” program, repositioning stores as public spaces open to the community rather than transaction-focused retail outlets. In related explanations, she mentioned that the purpose of stores is to educate, inspire, and connect communities, not merely to complete sales. “We want every store to be a place where anyone can walk in, learn, exchange ideas, and find inspiration.” Such language essentially redefined the role of the retail department within the organization.

For this reason, in her communications with the retail team around holidays, Angela Ahrendts rarely discussed sprints, goals, or numbers, instead deliberately bringing the conversation back to “people.” She reminded her team in one address that if a person feels respected and trusted at work, this state naturally reflects in their interactions with customers. “If you are treated well here, customers will feel it. That’s not something you train for; it comes from the state you’re in.”

For Angela Ahrendts, festivals are not times to accelerate performance but moments to check whether the culture remains in the right place. Her holiday messages are remembered not because they are warm but because they are highly consistent with her daily management choices.

When leaders repeatedly remind the organization what must not be sacrificed even during times “most easily dominated by numbers,” it becomes a predictable behavioral pattern. This predictability is key to the long-term accumulation of trust and reputation.

Herbert Diess: In Highly Uncertain Times, Stability Itself Is a Leadership Act

In 2020, Herbert Diess served as CEO of Volkswagen Group, facing multiple pressures from the pandemic impact, global supply chain disruptions, and an incomplete transition to electrification. For a company heavily reliant on physical manufacturing and international collaboration, the crisis permeated every production site and management level rapidly.

In his internal communications during the early stages of the pandemic, Herbert Diess did not rush to provide direction or promise results but first addressed the most apparent unease within the organization. In his remarks to employees, he clearly outlined the actual situation, stating that the scope and duration of the pandemic’s impact could not be accurately predicted and that leadership could not pretend to have everything under control. “How much impact this pandemic will have and how long it will last—we truly cannot provide reliable answers right now.” Such statements effectively drew a boundary for the organization, preventing uncertainty from spreading in the form of rumors or speculation.

Simultaneously, he repeatedly emphasized decision-making priorities. During the most severe phase of the pandemic, Volkswagen’s primary internal signal was not about capacity or goals but safety itself. Herbert Diess stated plainly in a public address to employees, “At this stage, the most important thing is ensuring the safety of employees and their families.” This statement was not about emotional comfort but clearly told the organization that the company would not, for the time being, use performance or output as the sole criterion for judgment.

This communication approach is particularly critical for large-scale manufacturing. When rules are unclear and information is incomplete, what employees fear most is often not bad news but not knowing whether the company will suddenly change standards. Diess chose to articulate the “unknown” clearly, thereby reducing psychological friction within the organization.

By year-end, in his holiday messages, Herbert Diess continued the same linguistic logic. Rather than reviewing achievements or looking ahead to the coming year, he deliberately focused on rest and peace, telling employees, “I hope you and your families can have a period of genuine rest to re-accumulate strength.” At the time, this was not a routine holiday greeting but a managerial choice—before the high uncertainty was resolved, the company chose to stabilize people’s state first.

Herbert Diess’ communication strategy did not lie in providing complete answers but in drawing clear boundaries at critical moments. When top decision-makers choose first to explain “what will not be required now,” psychological friction within the organization significantly decreases.

Extending this linguistic logic around the holidays equals reconfirming that the company would not quietly change evaluation standards before uncertainty was resolved. Stabilizing expectations, rather than making radical promises, became the most reputation-effective leadership act during that phase.

Mary Barra: Preserving Sustained Momentum for Long-Term Transformation

Mary Barra is the CEO of General Motors (GM) and a key decision-maker in the company’s electrification and organizational restructuring process. The transformation she has driven since taking office involves not only product shifts but also long-term changes affecting production lines, supply chains, and workforce structures. Against this backdrop, her internal communications have always been known for clear goals and execution orientation.

However, in her holiday messages, she deliberately adjusted the positioning of her language. Compared to her usual emphasis on progress and responsibility, she chose to temporarily set aside the language of transformation and address a more realistic issue: whether people have the space to recover and sustain during long-term, high-pressure transformation.

In one holiday message to all employees, she directly pointed out the difference of this moment, reminding the team not to treat the holiday as part of the transformation to be consumed. “Please, during this time, truly step away from work and return to the people who matter to you.” The function of this statement was not emotional encouragement but clearly drawing a line: the company does not expect continuous output from employees at this time.

Mary Barra articulated this choice even more directly in another internal letter. She noted that transformation is not a sprint but a process that depletes organizational energy over the long term. Without rhythm management, the first problem to arise would not be strategy but people. “One of leadership’s responsibilities is to ensure the team can endure transformation long-term, not just survive the next milestone.” Such expression shifted the conditions for transformation success from single outcome metrics to organizational endurance itself.

For highly goal-oriented companies, the value of such messages lies in clearly declaring that “pausing is permitted.” When top decision-makers clearly draw the line that certain time points will not be used to assess commitment or loyalty, the organization can later return to the battlefield fully at key junctures.

This is not about slowing down transformation but preserving endurance capability for it.

Ingvar Kamprad: Using Consistent Language So Values Need No Explanation

Ingvar Kamprad is the founder of IKEA and the earliest and most enduring definer of the brand’s culture. When the company was small, he controlled operational decisions; as it expanded internationally, he practically influenced how the organization understood “what can be done and what should not be done.” In this role, his holiday letters were never ceremonial speeches but moments when values were reaffirmed.

In multiple internal letters and public writings during the holidays, Kamprad repeatedly returned to the same set of keywords: life, family, and moderation. This was not to create a warm atmosphere but because he clearly knew that if the founder spoke differently during these times than usual, the organization would immediately detect inconsistency. When discussing “simplicity,” he directly pointed out that it was not a stylistic choice but a business choice. “Excessive complexity often makes people overlook what truly matters; simplicity instead makes values clear.” Such statements effectively tied lifestyle attitudes to business judgment.

In another letter, he also pulled “moderation” from the moral level to the management level. He reminded the management team that if the company lost respect for life itself during growth, it would ultimately lose understanding of people. “Moderation is not sacrifice but a choice of values.” This statement is repeatedly quoted not because it is moving but because it has long been consistent with IKEA’s choices regarding costs, design, and organizational structure.

For IKEA, such language is not limited to holidays but part of an ongoing governance logic. When the founder speaks the same language during festivals and daily operations, the organization does not need to guess “which values are merely rhetoric.” For this reason, Kamprad’s holiday messages never needed explanation; they simply reconfirmed one thing: wherever the company goes, values follow. Long-term, this consistency builds trust more effectively than any motivational slogan and is more easily recognized externally as a stable corporate character.

Festivals Amplify Long-Term Accumulated Reputation

For these corporate leaders, holiday communication is never an ancillary action but part of long-term positioning. When similar choices repeatedly appear at similar times, the organization gradually forms stable expectations, knowing which values will not be adjusted due to pressure, cycles, or market sentiment.

From public and media perspectives, such messages also produce effects. They do not rely on dramatic statements to attract attention but allow external parties to recognize a consistent judgment method even years later. For investors, partners, and potential talent, this verifiable leadership profile is often more persuasive than any single declaration.

During festivals like Christmas, this is merely a time when such judgment becomes more easily visible.

Ultimately, what these communications leave behind is not a quotable phrase but a long-term, verified behavioral pattern. When leaders choose to treat the organization in the same way during moments when there is no need to prove or urgently push forward, trust no longer comes from persuasion but from choices that are continually seen.

Recommend for you:

The Light He Brought to COP30: Ray Ko and the Story of Water and Hope